A variable provides us with named storage that our programs can manipulate. Each variable in C++ has a type. The type determines the size and layout of the variable’s memory, the range of values that can be stored within that memory, and the set of operations that can be applied to the variable. C++ programmers tend to refer to variables as “variables” or “objects” interchangeably.

A simple variable definition consists of a type specifier, followed by a list of one or more variable names separated by commas, and ends with a semicolon. Each name in the list has the type defined by the type specifier. A definition may (optionally) provide an initial value for one or more of the names it defines:

int sum = 0, value, // sum, value, and units_sold have type int

units_sold = 0; // sum and units_sold have initial value 0

Sales_item item; // item has type Sales_item (see § 1.5.1 (p. 20))

// string is a library type, representing a variable-length sequence of characters

std::string book("0-201-78345-X"); // book initialized from string literal

The definition of book uses the std::string library type. Like iostream (§ 1.2, p. 7), string is defined in namespace std. We’ll have more to say about the string type in Chapter 3. For now, what’s useful to know is that a string is a type that represents a variable-length sequence of characters. The string library gives us several ways to initialize string objects. One of these ways is as a copy of a string literal (§ 2.1.3, p. 39). Thus, book is initialized to hold the characters 0-201-78345-X.

C++ programmers tend to be cavalier in their use of the term object. Most generally, an object is a region of memory that can contain data and has a type.

Some use the term object only to refer to variables or values of class types. Others distinguish between named and unnamed objects, using the term variable to refer to named objects. Still others distinguish between objects and values, using the term object for data that can be changed by the program and the term value for data that are read-only.

In this book, we’ll follow the more general usage that an object is a region of memory that has a type. We will freely use the term object regardless of whether the object has built-in or class type, is named or unnamed, or can be read or written.

An object that is initialized gets the specified value at the moment it is created. The values used to initialize a variable can be arbitrarily complicated expressions. When a definition defines two or more variables, the name of each object becomes visible immediately. Thus, it is possible to initialize a variable to the value of one defined earlier in the same definition.

// ok: price is defined and initialized before it is used to initialize discount

double price = 109.99, discount = price * 0.16;

// ok: call applyDiscount and use the return value to initialize salePrice

double salePrice = applyDiscount(price, discount);

Initialization in C++ is a surprisingly complicated topic and one we will return to again and again. Many programmers are confused by the use of the = symbol to initialize a variable. It is tempting to think of initialization as a form of assignment, but initialization and assignment are different operations in C++. This concept is particularly confusing because in many languages the distinction is irrelevant and can be ignored. Moreover, even in C++ the distinction often doesn’t matter. Nonetheless, it is a crucial concept and one we will reiterate throughout the text.

Initialization is not assignment. Initialization happens when a variable is given a value when it is created. Assignment obliterates an object’s current value and replaces that value with a new one.

One way in which initialization is a complicated topic is that the language defines several different forms of initialization. For example, we can use any of the following four different ways to define an int variable named units_sold and initialize it to 0:

int units_sold = 0;

int units_sold = {0};

int units_sold{0};

int units_sold(0);

The generalized use of curly braces for initialization was introduced as part of the new standard. This form of initialization previously had been allowed only in more restricted ways. For reasons we’ll learn about in § 3.3.1 (p. 98), this form of initialization is referred to as list initialization. Braced lists of initializers can now be used whenever we initialize an object and in some cases when we assign a new value to an object.

When used with variables of built-in type, this form of initialization has one important property: The compiler will not let us list initialize variables of built-in type if the initializer might lead to the loss of information:

long double ld = 3.1415926536;

int a{ld}, b = {ld}; // error: narrowing conversion required

int c(ld), d = ld; // ok: but value will be truncated

The compiler rejects the initializations of a and b because using a long double to initialize an int is likely to lose data. At a minimum, the fractional part of ld will be truncated. In addition, the integer part in ld might be too large to fit in an int.

As presented here, the distinction might seem trivial—after all, we’d be unlikely to directly initialize an int from a long double. However, as we’ll see in Chapter 16, such initializations might happen unintentionally. We’ll say more about these forms of initialization in § 3.2.1 (p. 84) and § 3.3.1 (p. 98).

When we define a variable without an initializer, the variable is default initialized. Such variables are given the “default” value. What that default value is depends on the type of the variable and may also depend on where the variable is defined.

The value of an object of built-in type that is not explicitly initialized depends on where it is defined. Variables defined outside any function body are initialized to zero. With one exception, which we cover in § 6.1.1 (p. 205), variables of built-in type defined inside a function are uninitialized. The value of an uninitialized variable of built-in type is undefined (§ 2.1.2, p. 36). It is an error to copy or otherwise try to access the value of a variable whose value is undefined.

Each class controls how we initialize objects of that class type. In particular, it is up to the class whether we can define objects of that type without an initializer. If we can, the class determines what value the resulting object will have.

Most classes let us define objects without explicit initializers. Such classes supply an appropriate default value for us. For example, as we’ve just seen, the library string class says that if we do not supply an initializer, then the resulting string is the empty string:

std::string empty; // empty implicitly initialized to the empty string

Sales_item item; // default-initialized Sales_item object

Some classes require that every object be explicitly initialized. The compiler will complain if we try to create an object of such a class with no initializer.

Uninitialized objects of built-in type defined inside a function body have undefined value. Objects of class type that we do not explicitly initialize have a value that is defined by the class.

Exercises Section 2.2.1

Exercise 2.9: Explain the following definitions. For those that are illegal, explain what’s wrong and how to correct it.

(a)

std::cin >> int input_value;(b)

int i = { 3.14 };(c)

double salary = wage = 9999.99;(d)

int i = 3.14;Exercise 2.10: What are the initial values, if any, of each of the following variables?

std::string global_str;

int global_int;

int main()

{

int local_int;

std::string local_str;

}

To allow programs to be written in logical parts, C++ supports what is commonly known as separate compilation. Separate compilation lets us split our programs into several files, each of which can be compiled independently.

When we separate a program into multiple files, we need a way to share code across those files. For example, code defined in one file may need to use a variable defined in another file. As a concrete example, consider std::cout and std::cin. These are objects defined somewhere in the standard library, yet our programs can use these objects.

An uninitialized variable has an indeterminate value. Trying to use the value of an uninitialized variable is an error that is often hard to debug. Moreover, the compiler is not required to detect such errors, although most will warn about at least some uses of uninitialized variables.

What happens when we use an uninitialized variable is undefined. Sometimes, we’re lucky and our program crashes as soon as we access the object. Once we track down the location of the crash, it is usually easy to see that the variable was not properly initialized. Other times, the program completes but produces erroneous results. Even worse, the results may appear correct on one run of our program but fail on a subsequent run. Moreover, adding code to the program in an unrelated location can cause what we thought was a correct program to start producing incorrect results.

We recommend initializing every object of built-in type. It is not always necessary, but it is easier and safer to provide an initializer until you can be certain it is safe to omit the initializer.

To support separate compilation, C++ distinguishes between declarations and definitions. A declaration makes a name known to the program. A file that wants to use a name defined elsewhere includes a declaration for that name. A definition creates the associated entity.

A variable declaration specifies the type and name of a variable. A variable definition is a declaration. In addition to specifying the name and type, a definition also allocates storage and may provide the variable with an initial value.

To obtain a declaration that is not also a definition, we add the extern keyword and may not provide an explicit initializer:

extern int i; // declares but does not define i

int j; // declares and defines j

Any declaration that includes an explicit initializer is a definition. We can provide an initializer on a variable defined as extern, but doing so overrides the extern. An extern that has an initializer is a definition:

extern double pi = 3.1416; // definition

It is an error to provide an initializer on an extern inside a function.

The distinction between a declaration and a definition may seem obscure at this point but is actually important. To use a variable in more than one file requires declarations that are separate from the variable’s definition. To use the same variable in multiple files, we must define that variable in one—and only one—file. Other files that use that variable must declare—but not define—that variable.

We’ll have more to say about how C++ supports separate compilation in § 2.6.3 (p. 76) and § 6.1.3 (p. 207).

Exercises Section 2.2.2

Exercise 2.11: Explain whether each of the following is a declaration or a definition:

(a)

extern int ix = 1024;(b)

int iy;(c)

extern int iz;

C++ is a statically typed language, which means that types are checked at compile time. The process by which types are checked is referred to as type checking.

As we’ve seen, the type of an object constrains the operations that the object can perform. In C++, the compiler checks whether the operations we write are supported by the types we use. If we try to do things that the type does not support, the compiler generates an error message and does not produce an executable file.

As our programs get more complicated, we’ll see that static type checking can help find bugs. However, a consequence of static checking is that the type of every entity we use must be known to the compiler. As one example, we must declare the type of a variable before we can use that variable.

Identifiers in C++ can be composed of letters, digits, and the underscore character. The language imposes no limit on name length. Identifiers must begin with either a letter or an underscore. Identifiers are case-sensitive; upper- and lowercase letters are distinct:

// defines four different int variables

int somename, someName, SomeName, SOMENAME;

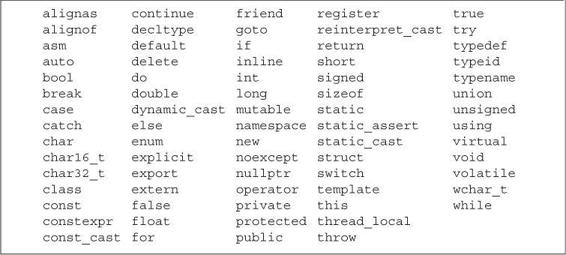

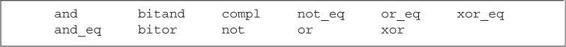

The language reserves a set of names, listed in Tables 2.3 and Table 2.4, for its own use. These names may not be used as identifiers.

Table 2.4. C++ Alternative Operator Names

The standard also reserves a set of names for use in the standard library. The identifiers we define in our own programs may not contain two consecutive underscores, nor can an identifier begin with an underscore followed immediately by an uppercase letter. In addition, identifiers defined outside a function may not begin with an underscore.

There are a number of generally accepted conventions for naming variables. Following these conventions can improve the readability of a program.

• Variable names normally are lowercase—

index, notIndexorINDEX.

• Like

Sales_item, classes we define usually begin with an uppercase letter.

• Identifiers with multiple words should visually distinguish each word, for example,

student_loanorstudentLoan, notstudentloan.

Exercises Section 2.2.3

Exercise 2.12: Which, if any, of the following names are invalid?

(a)

int double = 3.14;(b)

int _;(c)

int catch-22;(d)

int 1_or_2 = 1;(e)

double Double = 3.14;

At any particular point in a program, each name that is in use refers to a specific entity—a variable, function, type, and so on. However, a given name can be reused to refer to different entities at different points in the program.

A scope is a part of the program in which a name has a particular meaning. Most scopes in C++ are delimited by curly braces.

The same name can refer to different entities in different scopes. Names are visible from the point where they are declared until the end of the scope in which the declaration appears.

As an example, consider the program from § 1.4.2 (p. 13):

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

int sum = 0;

// sum values from 1 through 10 inclusive

for (int val = 1; val <= 10; ++val)

sum += val; // equivalent to sum = sum + val

std::cout << "Sum of 1 to 10 inclusive is "

<< sum << std::endl;

return 0;

}

This program defines three names—main, sum, and val—and uses the namespace name std, along with two names from that namespace—cout and endl.

The name main is defined outside any curly braces. The name main—like most names defined outside a function—has global scope. Once declared, names at the global scope are accessible throughout the program. The name sum is defined within the scope of the block that is the body of the main function. It is accessible from its point of declaration throughout the rest of the main function but not outside of it. The variable sum has block scope. The name val is defined in the scope of the for statement. It can be used in that statement but not elsewhere in main.

It is usually a good idea to define an object near the point at which the object is first used. Doing so improves readability by making it easy to find the definition of the variable. More importantly, it is often easier to give the variable a useful initial value when the variable is defined close to where it is first used.

Scopes can contain other scopes. The contained (or nested) scope is referred to as an inner scope, the containing scope is the outer scope.

Once a name has been declared in a scope, that name can be used by scopes nested inside that scope. Names declared in the outer scope can also be redefined in an inner scope:

#include <iostream>

// Program for illustration purposes only: It is bad style for a function

// to use a global variable and also define a local variable with the same name

int reused = 42; // reused has global scope

int main()

{

int unique = 0; // unique has block scope

// output #1: uses global reused; prints 42 0

std::cout << reused << " " << unique << std::endl;

int reused = 0; // new, local object named reused hides global reused

// output #2: uses local reused; prints 0 0

std::cout << reused << " " << unique << std::endl;

// output #3: explicitly requests the global reused; prints 42 0

std::cout << ::reused << " " << unique << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Output #1 appears before the local definition of reused. Therefore, this output statement uses the name reused that is defined in the global scope. This statement prints 42 0. Output #2 occurs after the local definition of reused. The local reused is now in scope. Thus, this second output statement uses the local object named reused rather than the global one and prints 0 0. Output #3 uses the scope operator (§ 1.2, p. 8) to override the default scoping rules. The global scope has no name. Hence, when the scope operator has an empty left-hand side, it is a request to fetch the name on the right-hand side from the global scope. Thus, this expression uses the global reused and prints 42 0.

It is almost always a bad idea to define a local variable with the same name as a global variable that the function uses or might use.

Exercises Section 2.2.4

Exercise 2.13: What is the value of

jin the following program?int i = 42;

int main()

{

int i = 100;

int j = i;

}Exercise 2.14: Is the following program legal? If so, what values are printed?

int i = 100, sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i != 10; ++i)

sum += i;

std::cout << i << " " << sum << std::endl;