The new and delete operators allocate objects one at a time. Some applications, need the ability to allocate storage for many objects at once. For example, vectors and strings store their elements in contiguous memory and must allocate several elements at once whenever the container has to be reallocated (§ 9.4, p. 355).

To support such usage, the language and library provide two ways to allocate an array of objects at once. The language defines a second kind of new expression that allocates and initializes an array of objects. The library includes a template class named allocator that lets us separate allocation from initialization. For reasons we’ll explain in § 12.2.2 (p. 481), using an allocator generally provides better performance and more flexible memory management.

Many, perhaps even most, applications have no direct need for dynamic arrays. When an application needs a varying number of objects, it is almost always easier, faster, and safer to do as we did with StrBlob: use a vector (or other library container). For reasons we’ll explain in § 13.6 (p. 531), the advantages of using a library container are even more pronounced under the new standard. Libraries that support the new standard tend to be dramatically faster than previous releases.

Most applications should use a library container rather than dynamically allocated arrays. Using a container is easier, less likely to contain memory-management bugs, and is likely to give better performance.

As we’ve seen, classes that use the containers can use the default versions of the operations for copy, assignment, and destruction (§ 7.1.5, p. 267). Classes that allocate dynamic arrays must define their own versions of these operations to manage the associated memory when objects are copied, assigned, and destroyed.

Do not allocate dynamic arrays in code inside classes until you have read Chapter 13.

new and Arrays

We ask new to allocate an array of objects by specifying the number of objects to allocate in a pair of square brackets after a type name. In this case, new allocates the requested number of objects and (assuming the allocation succeeds) returns a pointer to the first one:

// call get_size to determine how many ints to allocate

int *pia = new int[get_size()]; // pia points to the first of these ints

The size inside the brackets must have integral type but need not be a constant.

We can also allocate an array by using a type alias (§ 2.5.1, p. 67) to represent an array type. In this case, we omit the brackets:

typedef int arrT[42]; // arrT names the type array of 42 ints

int *p = new arrT; // allocates an array of 42 ints; p points to the first one

Here, new allocates an array of ints and returns a pointer to the first one. Even though there are no brackets in our code, the compiler executes this expression using new[]. That is, the compiler executes this expression as if we had written

int *p = new int[42];

Although it is common to refer to memory allocated by new T[] as a “dynamic array,” this usage is somewhat misleading. When we use new to allocate an array, we do not get an object with an array type. Instead, we get a pointer to the element type of the array. Even if we use a type alias to define an array type, new does not allocate an object of array type. In this case, the fact that we’re allocating an array is not even visible; there is no [num]. Even so, new returns a pointer to the element type.

Because the allocated memory does not have an array type, we cannot call begin or end (§ 3.5.3, p. 118) on a dynamic array. These functions use the array dimension (which is part of an array’s type) to return pointers to the first and one past the last elements, respectively. For the same reasons, we also cannot use a range for to process the elements in a (so-called) dynamic array.

By default, objects allocated by new—whether allocated as a single object or in an array—are default initialized. We can value initialize (§ 3.3.1, p. 98) the elements in an array by following the size with an empty pair of parentheses.

int *pia = new int[10]; // block of ten uninitialized ints

int *pia2 = new int[10](); // block of ten ints value initialized to 0

string *psa = new string[10]; // block of ten empty strings

string *psa2 = new string[10](); // block of ten empty strings

Under the new standard, we can also provide a braced list of element initializers:

// block of ten ints each initialized from the corresponding initializer

int *pia3 = new int[10]{0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9};

// block of ten strings; the first four are initialized from the given initializers

// remaining elements are value initialized

string *psa3 = new string[10]{"a", "an", "the", string(3,'x')};

As when we list initialize an object of built-in array type (§ 3.5.1, p. 114), the initializers are used to initialize the first elements in the array. If there are fewer initializers than elements, the remaining elements are value initialized. If there are more initializers than the given size, then the new expression fails and no storage is allocated. In this case, new throws an exception of type bad_array_new_length. Like bad_alloc, this type is defined in the new header.

Although we can use empty parentheses to value initialize the elements of an array, we cannot supply an element initializer inside the parentheses. The fact that we cannot supply an initial value inside the parentheses means that we cannot use auto to allocate an array (§ 12.1.2, p. 459).

We can use an arbitrary expression to determine the number of objects to allocate:

size_t n = get_size(); // get_size returns the number of elements needed

int* p = new int[n]; // allocate an array to hold the elements

for (int* q = p; q != p + n; ++q)

/* process the array */ ;

An interesting question arises: What happens if get_size returns 0? The answer is that our code works fine. Calling new[n] with n equal to 0 is legal even though we cannot create an array variable of size 0:

char arr[0]; // error: cannot define a zero-length array

char *cp = new char[0]; // ok: but cp can't be dereferenced

When we use new to allocate an array of size zero, new returns a valid, nonzero pointer. That pointer is guaranteed to be distinct from any other pointer returned by new. This pointer acts as the off-the-end pointer (§ 3.5.3, p. 119) for a zero-element array. We can use this pointer in ways that we use an off-the-end iterator. The pointer can be compared as in the loop above. We can add zero to (or subtract zero from) such a pointer and can subtract the pointer from itself, yielding zero. The pointer cannot be dereferenced—after all, it points to no element.

In our hypothetical loop, if get_size returns 0, then n is also 0. The call to new will allocate zero objects. The condition in the for will fail (p is equal to q + n because n is 0). Thus, the loop body is not executed.

To free a dynamic array, we use a special form of delete that includes an empty pair of square brackets:

delete p; // p must point to a dynamically allocated object or be null

delete [] pa; // pa must point to a dynamically allocated array or be null

The second statement destroys the elements in the array to which pa points and frees the corresponding memory. Elements in an array are destroyed in reverse order. That is, the last element is destroyed first, then the second to last, and so on.

When we delete a pointer to an array, the empty bracket pair is essential: It indicates to the compiler that the pointer addresses the first element of an array of objects. If we omit the brackets when we delete a pointer to an array (or provide them when we delete a pointer to an object), the behavior is undefined.

Recall that when we use a type alias that defines an array type, we can allocate an array without using [] with new. Even so, we must use brackets when we delete a pointer to that array:

typedef int arrT[42]; // arrT names the type array of 42 ints

int *p = new arrT; // allocates an array of 42 ints; p points to the first one

delete [] p; // brackets are necessary because we allocated an array

Despite appearances, p points to the first element of an array of objects, not to a single object of type arrT. Thus, we must use [] when we delete p.

The compiler is unlikely to warn us if we forget the brackets when we

deletea pointer to an array or if we use them when wedeletea pointer to an object. Instead, our program is apt to misbehave without warning during execution.

The library provides a version of unique_ptr that can manage arrays allocated by new. To use a unique_ptr to manage a dynamic array, we must include a pair of empty brackets after the object type:

// up points to an array of ten uninitialized ints

unique_ptr<int[]> up(new int[10]);

up.release(); // automatically uses delete[] to destroy its pointer

The brackets in the type specifier (<int[]>) say that up points not to an int but to an array of ints. Because up points to an array, when up destroys the pointer it manages, it will automatically use delete[].

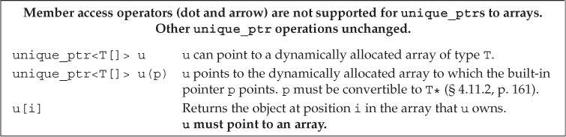

unqiue_ptrs that point to arrays provide slightly different operations than those we used in § 12.1.5 (p. 470). These operations are described in Table 12.6 (overleaf). When a unique_ptr points to an array, we cannot use the dot and arrow member access operators. After all, the unqiue_ptr points to an array, not an object so these operators would be meaningless. On the other hand, when a unqiue_ptr points to an array, we can use the subscript operator to access the elements in the array:

for (size_t i = 0; i != 10; ++i)

up[i] = i; // assign a new value to each of the elements

Table 12.6. unique_ptrs to Arrays

Unlike unique_ptr, shared_ptrs provide no direct support for managing a dynamic array. If we want to use a shared_ptr to manage a dynamic array, we must provide our own deleter:

// to use a shared_ptr we must supply a deleter

shared_ptr<int> sp(new int[10], [](int *p) { delete[] p; });

sp.reset(); // uses the lambda we supplied that uses delete[] to free the array

Here we pass a lambda (§ 10.3.2, p. 388) that uses delete[] as the deleter.

Had we neglected to supply a deleter, this code would be undefined. By default, shared_ptr uses delete to destroy the object to which it points. If that object is a dynamic array, using delete has the same kinds of problems that arise if we forget to use [] when we delete a pointer to a dynamic array (§ 12.2.1, p. 479).

The fact that shared_ptr does not directly support managing arrays affects how we access the elements in the array:

// shared_ptrs don't have subscript operator and don't support pointer arithmetic

for (size_t i = 0; i != 10; ++i)

*(sp.get() + i) = i; // use get to get a built-in pointer

There is no subscript operator for shared_ptrs, and the smart pointer types do not support pointer arithmetic. As a result, to access the elements in the array, we must use get to obtain a built-in pointer, which we can then use in normal ways.

Exercises Section 12.2.1

Exercise 12.23: Write a program to concatenate two string literals, putting the result in a dynamically allocated array of

char. Write a program to concatenate two librarystrings that have the same value as the literals used in the first program.Exercise 12.24: Write a program that reads a string from the standard input into a dynamically allocated character array. Describe how your program handles varying size inputs. Test your program by giving it a string of data that is longer than the array size you’ve allocated.

Exercise 12.25: Given the following

newexpression, how would youdelete pa?int *pa = new int[10];

allocator Class

An aspect of new that limits its flexibility is that new combines allocating memory with constructing object(s) in that memory. Similarly, delete combines destruction with deallocation. Combining initialization with allocation is usually what we want when we allocate a single object. In that case, we almost certainly know the value the object should have.

When we allocate a block of memory, we often plan to construct objects in that memory as needed. In this case, we’d like to decouple memory allocation from object construction. Decoupling construction from allocation means that we can allocate memory in large chunks and pay the overhead of constructing the objects only when we actually need to create them.

In general, coupling allocation and construction can be wasteful. For example:

string *const p = new string[n]; // construct n empty strings

string s;

string *q = p; // q points to the first string

while (cin >> s && q != p + n)

*q++ = s; // assign a new value to *q

const size_t size = q - p; // remember how many strings we read

// use the array

delete[] p; // p points to an array; must remember to use delete[]

This new expression allocates and initializes n strings. However, we might not need n strings; a smaller number might suffice. As a result, we may have created objects that are never used. Moreover, for those objects we do use, we immediately assign new values over the previously initialized strings. The elements that are used are written twice: first when the elements are default initialized, and subsequently when we assign to them.

More importantly, classes that do not have default constructors cannot be dynamically allocated as an array.

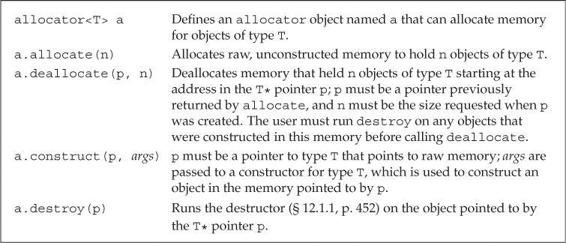

allocator ClassThe library allocator class, which is defined in the memory header, lets us separate allocation from construction. It provides type-aware allocation of raw, unconstructed, memory. Table 12.7 (overleaf) outlines the operations that allocator supports. In this section, we’ll describe the allocator operations. In § 13.5 (p. 524), we’ll see an example of how this class is typically used.

Table 12.7. Standard allocator Class and Customized Algorithms

Like vector, allocator is a template (§ 3.3, p. 96). To define an allocator we must specify the type of objects that a particular allocator can allocate. When an allocator object allocates memory, it allocates memory that is appropriately sized and aligned to hold objects of the given type:

allocator<string> alloc; // object that can allocate strings

auto const p = alloc.allocate(n); // allocate n unconstructed strings

This call to allocate allocates memory for n strings.

allocators Allocate Unconstructed MemoryThe memory an allocator allocates is unconstructed. We use this memory by constructing objects in that memory. In the new library the construct member takes a pointer and zero or more additional arguments; it constructs an element at the given location. The additional arguments are used to initialize the object being constructed. Like the arguments to make_shared (§ 12.1.1, p. 451), these additional arguments must be valid initializers for an object of the type being constructed. In particular, if the, object is a class type, these arguments must match a constructor for that class:

auto q = p; // q will point to one past the last constructed element

alloc.construct(q++); // *q is the empty string

alloc.construct(q++, 10, 'c'); // *q is cccccccccc

alloc.construct(q++, "hi"); // *q is hi!

In earlier versions of the library, construct took only two arguments: the pointer at which to construct an object and a value of the element type. As a result, we could only copy an element into unconstructed space, we could not use any other constructor for the element type.

It is an error to use raw memory in which an object has not been constructed:

cout << *p << endl; // ok: uses the string output operator

cout << *q << endl; // disaster: q points to unconstructed memory!

We must

constructobjects in order to use memory returned byallocate. Using unconstructed memory in other ways is undefined.

When we’re finished using the objects, we must destroy the elements we constructed, which we do by calling destroy on each constructed element. The destroy function takes a pointer and runs the destructor (§ 12.1.1, p. 452) on the pointed-to object:

while (q != p)

alloc.destroy(--q); // free the strings we actually allocated

At the beginning of our loop, q points one past the last constructed element. We decrement q before calling destroy. Thus, on the first call to destroy, q points to the last constructed element. We destroy the first element in the last iteration, after which q will equal p and the loop ends.

Once the elements have been destroyed, we can either reuse the memory to hold other strings or return the memory to the system. We free the memory by calling deallocate:

alloc.deallocate(p, n);

The pointer we pass to deallocate cannot be null; it must point to memory allocated by allocate. Moreover, the size argument passed to deallocate must be the same size as used in the call to allocate that obtained the memory to which the pointer points.

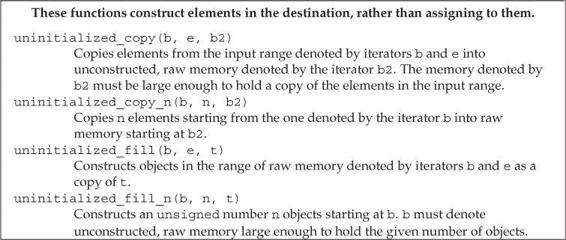

As a companion to the allocator class, the library also defines two algorithms that can construct objects in uninitialized memory. These functions, described in Table 12.8, are defined in the memory header.

Table 12.8. allocator Algorithms

As an example, assume we have a vector of ints that we want to copy into dynamic memory. We’ll allocate memory for twice as many ints as are in the vector. We’ll construct the first half of the newly allocated memory by copying elements from the original vector. We’ll construct elements in the second half by filling them with a given value:

// allocate twice as many elements as vi holds

auto p = alloc.allocate(vi.size() * 2);

// construct elements starting at p as copies of elements in vi

auto q = uninitialized_copy(vi.begin(), vi.end(), p);

// initialize the remaining elements to 42

uninitialized_fill_n(q, vi.size(), 42);

Like the copy algorithm (§ 10.2.2, p. 382), uninitialized_copy takes three iterators. The first two denote an input sequence and the third denotes the destination into which those elements will be copied. The destination iterator passed to uninitialized_copy must denote unconstructed memory. Unlike copy, uninitialized_copy constructs elements in its destination.

Like copy, uninitialized_copy returns its (incremented) destination iterator. Thus, a call to uninitialized_copy returns a pointer positioned one element past the last constructed element. In this example, we store that pointer in q, which we pass to uninitialized_fill_n. This function, like fill_n (§ 10.2.2, p. 380), takes a pointer to a destination, a count, and a value. It will construct the given number of objects from the given value at locations starting at the given destination.

Exercises Section 12.2.2

Exercise 12.26: Rewrite the program on page 481 using an

allocator.